The Mechanics of Prong Collars

The topic of prong collars can be controversial and emotive; this article will discuss some of the mechanics of prong collars, dissecting erroneous or misleading claims so you can make a more informed choice when selecting equipment for your dog.

Disclaimer: Australia has laws surrounding the use and importation of prong collars. This article will not discuss the moral, ethical, or legal concerns surrounding their use; instead, this article is designed to educate handlers on the mechanics of prong collars and challenge some popular claims. It is up to you to make an informed decision as to what is best for your dog within the bounds of the law and your own moral and ethical judgement.

At Canine Body Balance, we advocate for the dog, and one of the ways we do this is by educating owners. The use of prong collars falls outside the scope of our services, and it is not something we advocate for; however, we are happy to engage with customers seeking to utilise our therapeutic services to better their dogs’ lives, regardless of their current choice of equipment.

Prong Collars

Popular in some dog training circles and despised in others, discussions on the use of prong collars can divide communities. These discussions can be ripe with strong emotive language and misleading claims. This article, written by a qualified mechanical engineer and canine therapist, explains what they are, what they are designed to do, and how they work, or, more generally, the mechanics of prong collars.

What is a prong collar?

The prong collar is a type of collar used by some dog handlers or trainers; instead of having a flat surface that is in contact with the dog’s neck, it has prongs. Prongs are essentially protrusions or bits that are raised above the collar surface. There are several types of prong collars on the market, which are sometimes referred to as pinch collars or constriction collars.

The prong collar is specifically designed to apply force in concentrated areas on the dog’s neck; that is, the application of force through the tip of each prong is in a constrictive manner. In the more traditional style, the prongs apply force when the leash is pulled; without any leash pressure, the links rotate to release pressure from the dog’s neck. However, the amount of force the dog is subjected to will be determined by the collar’s fit, the style, and how much force is applied through the lead. Generally, the prongs are always in contact with the dog’s neck; it is just the pressure that varies.

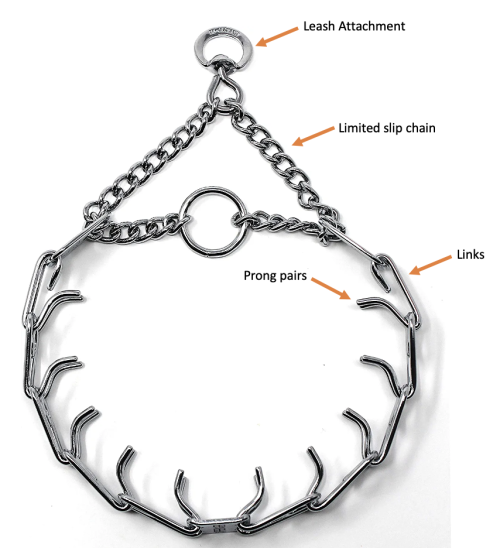

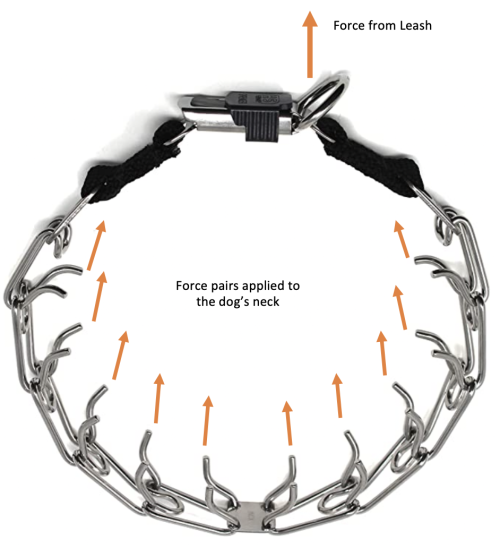

There are several components to the prong collar: the leash attachment, the limited slip chain, and the prong links. The leash attaches to a ring connected to a small loop of chain. This chain slides through the loops on both ends of the prong links and functions as a tightening and loosening mechanism. This slip chain mechanism initiates constriction, which reduces the effect of forces being highly concentrated on the dog’s neck directly opposite the lead; in other words, the limited slip chain aids in distributing the force from the leash around the collar into each prong. When the leash is pulled, slack in this chain is removed, thereby decreasing the circumference of the collar, and constricting around the dog’s neck.

As the collar tightens, the prong links are activated or rotated. These prongs may be aligned in pairs, two side by side on each link, or as a single protrusion. When the limited slip chain is tightened, the prong links pivot such that the prongs deliver the force in an area concentrated to the tip of each prong. The length of the lever arm on each link and the length of each prong will impact how the leash tension is delivered into the dog’s neck.

Why Are Prong Collars Used?

Prong collars fall into the category of “training tool,” which means they are essentially a piece of equipment that some people choose to use for training their dogs. However, a training tool used without correct training will likely result in the dog experiencing pain and/or injury without fixing the problematic behaviour that initially caused the handler to implement the tool.

Leashing pulling

A typical example of why some people choose to use prong collars is to eliminate or reduce unwanted strong leash pulling. Without the correct training, dogs may inadvertently learn that pulling on the leash gets them to where they want to be. This behaviour is readily reinforced when they pull and subsequently reach their destination or at least get closer to it. Even small dogs can become very strong at pulling without correct training.

The high reinforcement rate of leash pulling can quickly escalate this behaviour into a physical problem of power imbalance (discussed below). This creates a risk of injury to both the dog and the handler. The prong collar’s highly concentrated forces mechanically alter this power imbalance (in favour of the handler). However, the likelihood of poor outcomes increases significantly when the handler cannot use this power advantage to alter the behaviour. The original problem can be exacerbated, and the risk of physical and psychological injury to the dog is drastically increased.

Increasing the force applied to the dog’s neck increases the likelihood of physical and psychological injury. It also increases the impact of injury; stronger forces result in more damage. Thus, there is a high to extreme risk of injury through incorrect use of prong collars. For instance, if the dog learns to pull harder, which is “possible” to “very likely” if misused, then the potential outcome is “major” to “catastrophic.” In this case, dog owners may seek a higher power advantage through other means, such as an electronic collar; thus, the risk continues to escalate.

Force Corrections

Others use prong collars as a device to deliver corrections; in some circles, this may be common for reactive dogs. Corrections are deployed through the applications of force: the leash is pulled such that the collar tightens around the neck, with the prongs activating and concentrating the force load into the dog via the tip of each prong. These corrections may last for either a short duration (sometimes referred to as a “pop of the leash”) or for a longer duration until the dog stops the unwanted behaviour. This is not what we advocate for—it is just a summary of how some dog trainers or dog owners use the collars.

The application of prong collar corrections is synonymous with a power imbalance; by concentrating the forces at the end of each prong, the handler increases the amount of force the dog receives in small areas around the neck. Whether those corrections are momentary or sustained, this type of collar is intended to give the handler a mechanical advantage to their strength.

What are Prong collars made from?

Traditional Prong Collar

The prong collar’s most well-known and popular style is the traditional Herm Sprenger. This collar is made of metal—typically stainless steel, a robust material with high strength and corrosive resistance. With its high yield strength, this material resists bending and fracturing in the intended application, allowing the collar to efficiently deliver force to the dog—whose soft tissue must yield. However, excessive force and repeated disassembly can cause the prongs to weaken and bend beyond their elastic limit. This reduces their structural integrity and can potentially damage the prongs, which poses a risk to the dog.

Cheaper steel is sometimes used in the manufacturing of these prong collars, in which case it will likely be chrome plated. The thin layer of chrome provides an oxidative barrier that prevents rusting of the steel. However, if this chrome plating is damaged, corrosion will begin, and areas of the protective chrome layer exposed to damp or salty conditions may start to bubble, flake, or peel. A corroding collar of any type should not be used on a dog, as small amounts of metals are leaving the collar and will migrate onto the skin and coat of the dog, potentially compromising their health.

The prongs on the Herm Springer-style collars are typically rounded, and either left bare or covered with a vinyl rubber end cap (PVC). These coverings marginally increase the surface area in contact with the dog’s neck, which would have an effect of marginally decreasing the force at each point. Since these coverings are flexible and more easily deformed than the steel, they may provide a slight dampening effect (their elastic deformation absorbs some of the force—overall, it is negligible). A final feature to note is that these end caps are typically black and have a different specific heat capacity than the metal. This means that how quickly they heat up and how much heat energy they store differs from the rest of the collar. Be mindful of using these on hot days in direct sunlight, as they may become hot.

Some people choose to cover their prong collar with a flat nylon collar. This is generally done for two reasons: discretion and safety. As mentioned earlier, using prong collars can be divisive, so people may choose to be discrete about their choice. Regarding safety, the traditional prong collar can, under some circumstances, pop open, which might otherwise leave the dog “uncontrolled” and “off-leash.” So, they chose to use a covering to reduce the risk of the collar disassembling. The issue with these coverings is that they alter the prong links’ behaviour, reducing the links’ ability to rotate. The nylon cover makes the prong collar more rigid, impacting how the force is applied and released on the dog’s neck.

Variations of the Traditional Prong Collars

There are many variations of the traditional prong collar on the market. Some replace the metal limited slip chain with nylon webbing and a quick-release buckle (either in metal or rigid plastic).

Prong collars without a limited slip function

When the limited slip function is eliminated, there is a drastic impact on how the prong collar works. Rather than constriction, the collar operates by jabbing the prongs into the neck, with a high-pressure area of force applied to the dog’s neck opposite to the leash. Since the limited slip function allows the forces to be more evenly distributed through each prong around the collar, removing this function means the forces are delivered in higher and lower concentrated areas. An increase in applied force increases the risk of injury but reduces the power imbalance; removing the limited slip function significantly increases the likelihood of injury.

Prong Collar with QUICK-RELEASE buckle

Any time components are changed, we need to reassess how the collar functions and what is the weakest part. If the premise of using a prong collar is to increase the dog owner’s power advantage, then care must be taken to ensure the buckle is sufficiently rated for the applicable loads. Plastic clips can weaken over time and with exposure to UV light, solvents, and grit, such as dirt or sand, so they do need to be checked regularly for cracks, as any breakage to the plastic buckle (on any collar, not just prong collars) is catastrophic, i.e., the collar is rendered inoperable.

When a quick-release buckle is placed in series with the prong links, it can alter the limited slip functionality. Some of these collars have an additional ring so that the limited slip function can be bypassed. Still, even when the dog owner chooses to engage the limited slip function, the rigid buckle alters the ability of the collar to constrict evenly. When there is uneven constriction, the forces applied to the dog’s neck through the prongs will also be uneven.

Other Styles of the Prong collar

There are other types of prong collars on the market. Some are made from rigid plastic, and others are metal. All of these collars are segmental, and the ability for each segment to rotate is imperative for the correct function of these collars.

Things to consider are:

The amount of surface area in contact with the dog’s neck when force is applied. The smaller the prong tip, the higher the concentration of force.

The number of prongs: fewer prongs equate to a high concentration of force at each prong; more prongs mean there is a greater area in contact with the dog’s neck, so the force load at each prong is reduced.

The protrusion shape: generally, the plastic prong collars and even the metal neck-tech collars use flat triangular-shaped prongs. Using a flat prong reduces the surface area - which, as discussed above, increases the point force to the dog’s neck. However, the pointier an object is, the more likely it is to break the skin or cause bleeding under the skin and damage the dog; ensuring that any prong is rounded and free from burrs is essential.

The ability of the prong links to rotate: this affects the action of the links and how they apply and release pressure

The respective distances between the rotation point, prong protrusion, and length of the prong link. All of these affect the magnitude of the output force into the dog’s neck.

Claims about prong collars

Claim: “Prong collars apply even pressure to the dog’s neck.”

False: This claim is false; prong collars work by applying concentrated forces at points around the dog’s neck. The tips of the prongs are in contact with the dog’s neck when force is applied through the leash. It is through these prong tips that the force is applied to the dog. Therefore, there are areas of high concentration force (at the prongs) and areas of zero or low force in areas other than the prongs. Depending on the collar’s design, the forces applied through each prong may be similar, or there may be certain prongs around the circumference that deliver a high concentration of force.

Claim: “Prong collars are safe to use because they don’t bust a balloon.”

False: This claim has been made famous in videos and a submission to the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Department of the Government of Western Australia. However, a balloon’s properties are significantly different from that of a dog’s neck. Notably, balloons are highly elastic in nature; bouncing or pressing a prong collar on a balloon does not provide any measurable indication of the forces transmitted through the leash or prongs, nor does it measure the impact on the dog. This experiment is meant to deceive the viewer into believing that the prong collar is safe to use on a dog. Scientifically, however, one cannot deduce that a prong collar is safe to use on a dog because the balloon in the video experiment did not burst. From a mechanical perspective, the balloon experiment is mechanically misleading. Viewers can better understand the science to realise that the claim is false by reading about how prong collars work further along in the article.

Claim: “A Prong collar will save your dog’s life.”

Misleading: This is a blanket statement that may or may not be relevant or accurate for the person reading or hearing the claim. Because it is directed at the reader, people can feel compelled to believe it, and perhaps they act on that, and if the result is positive, then the seemingly prophetic statement comes true. But what if the handler never heard or read this statement and took a different course of action that also resulted in a positive outcome? Then the statement would be false.

Claim: “Prong collars are the most humane training tool.”

False: So, let’s break down what humane means. The definition is to have compassion or benevolence (kindness). This tool does not offer compassion or kindness—it is simply a tool. As with any tool, it can be used in many different ways, including intentionally or inadvertently inflicting harm. However, this statement essentially compares the prong collar to all other training tools, so let’s look at what other tools trainers might use. Toys and treats are two training tools that you might instantly think are more humane, and they likely are, when used humanely. A tool or piece of equipment does not in and of itself offer compassion or kindness—it is how the tool is used. Humane treatment comes from the handler and not the device. Further, the application of prong collars is designed to increase the force applied to the dog—one would need to question if kindness is the application of corrections through concentrated forces.

Claim: “It is one of the safest collars for dogs.”

Misleading: The word “safest” is highly subjective in this sentence. To analyse the claim, there needs to be a definition of the criteria that each collar is objectively measured against to determine if prong collars are safe or one of the safest. Considering there are many variations of the prong collar that differ in their mechanical behaviour and delivery of force, it is apt to say that the statement is at the least, misleading.

How do Prong Collars Really Work?

As discussed above, how the prong collar operates can be affected by several factors. First, let’s start by looking at Power Imbalance and what is meant by that.

We will start by breaking down the equations:

Power = Work/time

Work = Force x Displacement

A simple definition of Force is that it acts on an object to move it.

Displacement is how far something has moved.

If we look at the scenario of a dog pulling on the leash, it uses force to move the owner from their original location to the location of the desired object or scent. Applying force to move a distance is work—the dog works hard to drag the owner along.

We can then determine how much power the dog used by dividing their work by the amount of time they engaged in this “work.” The longer they work (or pull the owner along), the more power they use. If the dog repeats this behaviour, they will get stronger, and their ability to “work” will become easier. In other words, they will become more powerful.

In this scenario, the power imbalance increases in favour of the dog. Initially, the dog was pulling the owner, but now they have built up strength and endurance; they can pull harder for longer.

So why do some dog owners use prong collars when there is a power imbalance? These collars use the dog’s power against them, causing the prongs to tighten on the neck and apply high-pressure forces at the tips of each prong. Depending on the magnitude of force delivered to the dog’s neck, it can cause discomfort, pain, or injury.

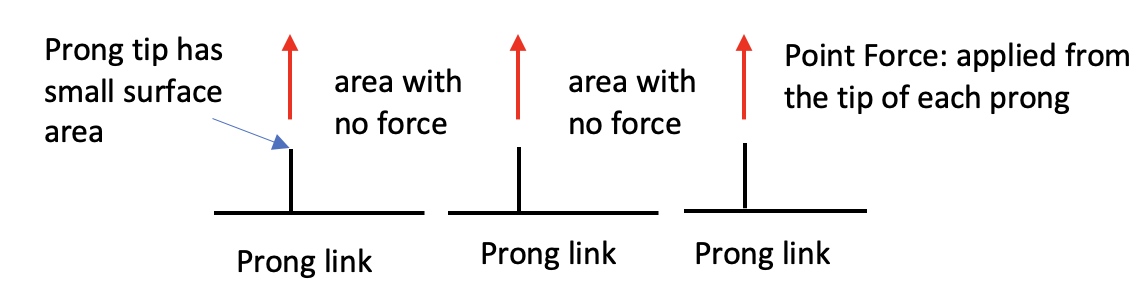

To understand why there are high-pressure forces at the tips of each prong, we need to look at Pressure and surface area:

Pressure = Force /Area

The same amount of force spread over a larger area will be lower in pressure than when the area is diminished. Prong collars have a low amount of surface area in contact with the dog’s neck, which means the pressure applied to the dog’s neck is high at the tip of each prong. The smaller the tip of the prong, the smaller the area in contact with the dog’s neck, and the higher the pressure.

Lever arm & Link length

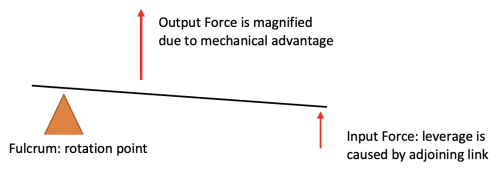

It was mentioned earlier in this article that the length of the prongs and links would affect the forces applied to the dog’s neck. So, let’s have a look at lever arms: levers transmit torque.

The point of rotation is called the fulcrum, and it sits at the end of the link. The lever arm is attached to the adjoining link, and the prongs sit somewhere in between the load application and the fulcrum; this makes it a class two lever. The benefit of a class two lever is that there is always a mechanical advantage greater than 1, which means that the force applied to the dog’s neck is greater than the effort used to move the link. It is the torque equation that helps explain this.

Torque = Force x Distance

We can see now that the length of the links and prong arms (or their distance values) will directly impact the torque and, thus, the output force.

To sum it up, the prong collar is designed to mechanically maximise output forces into the dog’s neck with minimal handler input, thus gaining a power advantage over the dog. This means that using these collars is likely to cause the dog pain since there is a high point load force at the tip of each prong which clamps into the soft tissue.

The risk of pain or injury increases when using a prong collar that omits the slip chain or has an ineffective slip chain. These collars distribute the forces more unevenly through the prongs than the traditional prong collar with a slip chain.

If you are still wondering, 'How do prong collars work?' or you want to delve further into the mathematics involved with how prong collars work. Then join us in the video below. You will learn how to apply mathematical equations to determine how much force is applied to the dog's neck through each prong.

Article Edited by: Messenger’s Memos

Leave a comment